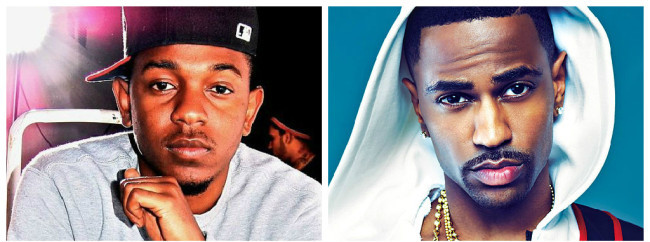

(Photos: Google Images)

What if anything is to be gleaned from the recent news that within the first three months of 2015 no less than 3 rappers have topped the Billboard 200 list? If you’re keeping track, that would be Kendrick Lamar in pole position with To Pimp a Butterfly, Drake with If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late, and Big Sean’s Dark Sky Paradise. Clearly this is a stellar first quarter for the perennially “dead” genre of hip-hop, illustrating that those incessantly ranting of its demise are in essentially the same company as climate change deniers. Hip-hop, like its guitar-driven cousin metal, appears to be settling into the global landscape as an eternal window into the soul of testosterone fueled young men and the women who love and emulate them.

Now clearly, public infatuation with certain genres shifts. The “Year of Rock” is inevitably replaced with the “Year of EDM” or “Year of Hip-hop” or “Year of Country” or whatever fashion surfaces from the primordial ooze of the zeitgeist. But why do certain genres come into fashion to begin with? What can they tell us about our present state of mind and cultural trajectory?

Over the last year we’ve witnessed a rebirth of Black consciousness after the stupefied post-racial haze following President Obama’s first election. For a moment, the country breathed a collective sigh of relief as centuries-old tensions appeared to evaporate within the span of a single political cycle. Cracks in this facade began to materialize almost immediately but such was the strength and naïveté of the recently dubbed “coalition of the ascendant” that we were willing to overlook them.

Then Trayvon Martin’s killer was exonerated despite overwhelming evidence of culpability. We watched a man beaten to death in NYC by cops and get off without so much as a slap to the wrist. By the time Ferguson arrived, we were ready to throw our hands up, facts in hand or not, and take it to the streets to protest the simple assertion that black lives matter.

Over that time, I have seen two distinct reactions from the Black artistic community. On one hand, you have those representing the New Blackness—those post-racialists clinging to the fiction that systemic racism has been supplanted by, at worst, a pernicious classism; ignoring entirely the volumes of evidence, some released as recently as last week, that collective disparities between blacks and whites are still as chasmic as ever. The other side, largely marginalized over the last decade, has remained unconvinced. The artistic offspring of Public Enemy, Tupac, and the Native Tongues movement—best typified by the hyper-fluency of a Kendrick Lamar—are increasingly finding an audience eager to wash the taste of indifference and false equivalence from their pallets.

The reason for this new hunger for reality-based rap cannot be limited to purely domestic causes. All around the world, movements forged from the frustration of the ignored, the marginalized and oppressed are upsetting the long-held balance of power. The Arab Spring, initially hailed for its promise of non-violent change in the Middle East, has given way to ISIS, Boko Haram, and bombings in the very streets where peaceful protesters once marched. From all over the world, young people exhausted with stasis have chosen violence and upheaval in preference to the droning platitudes of a one-size fits all New World Order. Domestically, millennials bashed over the head with dwindling hopes of advancement in the corporate world are creating their own paradigms, disrupting established industries, confronting previously impervious institutions, and all around raising hell in the name of a broken promise.

Is there any doubt as to why an art form like rap, with its origin in poverty stricken black and Latino neighborhoods, resonates so strongly? Is there any doubt why Big Sean’s aspirational Dark Sky Paradise, its very title drenched in conflict, resonates as a battle cry for anyone who has longed for the fabled good life—even at the potential expense of one’s soul. This theme recurs in both Dark Sky as well as TPAB—this sense that success is inherently problematic. It’s a reiteration of the old rap adage, “more money, more problems,” and even older, “money is the root of all evil.” Success in the context of Dark Sky is passage out of soul-crushing deprivation, but also a removal from the context that made such success possible. It’s the loss of trust, family and identify. You can practically here the desperation in Big Sean’s voice when he concludes in “Outro.” “Say I’m hard to get in contact with/oh, is that true/But what about now?/ 313-515-8772, bitch, call me.”

The same desperation is even clearer in Kendrick’s latest opus, weaving throughout the entire tapestry and perhaps most poignantly in “u” where K-Dot assumes the role of a forsaken homie. Even Drake, who largely eschews direct political commentary, seems obsessed with establishing his geographic bona fides and the criteria by which trust—whether to friends, business associates or women—can be extended. His world is an insular one framed by an absent father and a maniacal desire to be viewed as a man, even as he is dogged by boyish vices and insecurities.

This may very well be another Year of Rap, but there are still three more quarters to go. Nevertheless, even at this point, there’s very little risk in asserting that this latest crop of work from rap’s currently senior class is a complex mural of masculine ego, fear of erasure, and a desire to reconnect with a community that they fear may have deserted them. Or worse, may not be up the challenge of following them into the stratosphere.

Nyaze Vincent is a creative professional living in Los Angeles who moonlights as a musician when not helping clients navigate the tumultuous landscape of social media and digital production. Follow him on Twitter @ghettosavant.