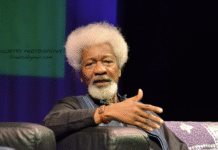

(Photo Credit: Donna Akiba Harper, Ph.D.)

Sonia Sanchez likes to talk about how peacekeeping can save communities. The profound poet laureate and author of Home Coming and Homegirls and Handgrenades stopped by Spelman College’s Sisters Chapel on Aug. 25 for an afternoon reading promoting the importance of humanity.

Her spirited presentation – equal parts harmonic poetry, hip slang, personal narratives, family portraits, a stack of books and topped with tranquil pearls of wisdom – was a call to the audience to uplift each other. Sanchez makes the crowd repeat after her several times.

“Promise that you will not twist, curl your tongue or say anything negative about anybody. Don’t destroy each other with gossip. You have no right to destroy people with your tongue,” says Sanchez.

The Black Arts Movement icon who wears thick shoulder length gray dreadlocks has a knack for storytelling. Sanchez, who pioneered organizing the first ever Black Studies Department while teaching at San Francisco State University, once overheard a male colleague insist that a woman’s commitment to the home would take precedence over being a university professor. The former Spelman Poet-in-Residence and honorary degree holder stresses to the majority young women audience to not allow sexism to affect their potential to succeed.

“You go out into a world not necessarily ready to greet you. You need to be tough. This is a world that will swallow you whole and think nothing else about it. Don’t ever let them give you left-handed compliments. They hope we don’t have a conversation about what it means to be human. We need to tell people what’s really bothering us,” says Sanchez.

A purple shawl draped across her shoulders, Sanchez periodically sips from a bottle of FIJI Water. She paces across the stage whether she’s behind the podium or not. Every word the orator speaks completes either a stanza or a quote. She pulls poems from her towering stack of books. Mid-performance, the dramatist starts to rock and incline her body to the rhythm of her poetry.

The 78 year-old Temple University Professor Emeritus addresses all of her students as brothers and sisters. She also requires students to frequently work in group activities. Sanchez’s methodology, she says, reminds students how sacrifices and teamwork are vital for empowering communities.

“We had to continue this fight for justice and jobs. People put their lives on the line so you can do that. Do not hurt each other. Don’t have any kind of disdain for each other. We love you, and we expect great things out of you. Whatever job you do, do it well and with the history of your ancestors,” says Sanchez.

Sanchez remembers raising her black students’ eyebrows for addressing every student as brother or sister. Working in groups, she adds, stresses the importance of accountability. “It changed the course of how students perceived one another. They were teaching to protect each other. If one person fails, we all fail,” says Sanchez.

These days, Sanchez is proud of having a peace haiku mural put up in Philadelphia. She’s working on having various museums and galleries (including Spelman’s campus) feature similar peace haiku benches with contributions from her neighbors and fellow poets.

For Sanchez, peace haiku works much like the students interacting with each other because both encourage productive citizenship. “You got to make your way in America. You defend yourself. You defend who we are,” says Sanchez.

This post was written by Christopher A. Daniel, pop cultural critic and music editor for the award -winning news site The Burton Wire. He is also a contributing writer for Urban Lux Magazine and Blues & Soul Magazine. Follow Christopher @Journalistorian on Twitter.

Like The Burton Wire on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter @TheBurtonWire.